Serve and volley is not dead; it’s as efficient as ever when it’s done right

The days of top players using the tactic on every first and second serve may be gone but if it’s used at the right times, serve and volley remains as useful as ever

© AI / Reuters / Panoramic

© AI / Reuters / Panoramic

As the first Grand Slam event of the year begins in Melbourne, players at the Australian Open will be battling it out for glory, pitting their wits against their opponents. Most of it will be done from the baseline, as it has been for 20 years, the days of Stefan Edberg, Pat Cash, Pat Rafter and co charging into the net a distant memory.

And yet, with almost everyone effectively doing the same thing, for any young player coming onto Tour these days, the opportunity to stand out is small. Doing what everyone else does, but better, is far from easy. It’s partly (but only partly) why Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic (with Andy Murray added in), have dominated the biggest tournaments for the best part of two decades.

Advances in string technology have made it easier for returners to put heavy topspin on the ball and send it down at the feet of the onrushing volleyer. The gradual homogenisation of court surfaces, with court speeds slower than ever, has been a key factor. Throw in the physicality of the game and the subsequent reduction in the number of players even trying to serve and volley and it’s easy to see why it’s heading for extinction.

And yet, it’s tempting to wonder: could it be done? Could someone with the physicality of Boris Becker, the serve of Pete Sampras, perhaps taller and stronger, come along and make it work? It began with a question on social media, which prompted some interesting replies.

Former world No 1 Yevgeny Kafelnikov, a baseliner of the highest order but who used to try to serve and volleyer on the (then) slick grass at Wimbledon, said it would be impossible.

Ivan Ljubicic, the former world No 3 and now coach of Roger Federer, agreed, pointing to the advances in string technology as the main reason why not.

Journalists weighed in, too, with Darren Walton, the long-time sports correspondent at AAP (the Australian Associated Press), pointing to a moment in time when Roger Federer, who began his career serving and volleying on first and second serve, at Wimbledon, gave up the ghost of serve and volley.

Pat Rafter: “The strings have changed the game”

Where better to go, though, than straight to one of the very best serve and volleyers of his or any generation. Aussie Pat Rafter served and volleyed his way to the world No 1 ranking, his brilliant kick serve and stunning net coverage good enough to win him back to back US Open titles in 1997 and 1998.

Had it not been for Pete Sampras (2000) and Goran Ivanisevic on that unforgettable Monday in 2001, he would also surely have been a Wimbledon champion, a title his game deserved.

In an interview with Tennis Majors, Rafter said it was hard to imagine someone being as successful these days.

“It doesn’t really appear to be conducive to play that game anymore,” Rafter said in a telephone call from his home in New South Wales. “It’s a strange evolution of a game. I don’t know where it goes to. As people get bigger, taller, stronger, what happens to the size of the court? The height of the net, et cetera, et cetera. You know, we’re not 5ft 7in anymore, we’re not Ken Rosewall and Rod Laver.

“I think the string has really stopped the way the game can be played, (allowing players) to generate the power and the pace and spin from being right off court. When you had someone off court, it was, go to the net, put the volley away. Or it was a defensive lob. These guys, they’re great athletes, they’re better athletes, and the technology has allowed them to make those shots.

I don’t know how you teach someone to serve and volley now

Pat Rafter

“I speak to Goran, apparently Wimbledon’s been oversowed to where the grass grows upright, it’s not just flat,” he said. “Goran just said, you should see how slow it is out here. I mean, the balls were always heavy at Wimbledon, but the court was quick. (Compare) the way the court would wear in the ’90s and have a look at the way the court looks now, it is so green, that whole middle of the court.”

“In the 90s, the whole middle part was ripped up in a T section, where you ran in, split step and went either side. It would be very, very difficult. I don’t know how you teach someone to serve and volley.”

Rafter recalled a particular match in his career when he realised that the strings were making his life harder and harder.

“I remember playing Gustavo Kuerten in the finals of Cincinnati, which was hot and fast.” he said. “I lost one and two. He was about six metres behind the baseline, reeling off winners. I’d do a big kick serve, out wide, and I’m just going, what is going on here? I would presume that would be a very similar situation to how it would be right now. It was coming in when I was leaving. Really hard to imagine how it would go. I reckon it would be bloody horrible.”

And yet, perhaps it is possible.

Cressy blazing a lone serve and volleying trail

While the likes of French-born American Maxime Cressy is one of the few players on the men’s Tour playing serve and volley. Cressy, who reached the final of the warm-up event in Melbourne recently, has improved his ranking from No 168 to No 75. At 6ft 6in, he’s not a giant but his style is causing problems for opponents.

Cressy, who grew up in France, went to college in the United States and says he feels half-French, half-American. The 24-year-old tested Rafael Nadal in their Melbourne final and the newcomer could sense the Spaniard was not enjoying it.

“I actually thought that it was working really well, especially even though I was a little tight, I still thought that he wasn’t comfortable,” he said. “He wasn’t feeling very comfortable returning.

“I feel it’s very efficient because it puts the player not in their safety zone, and I believe it’s going to be efficient against everyone. I played a lot of players and haven’t really seen many guys actually enjoy playing it, that kind of style. I’m very happy about it.”

Is it worth serving and volleying? The stats say yes

No one expects people to start serving and volleying flat out, first and second serve, on every surface. But Craig O’Shannessy, the coach and stats guru behind Brain Game Tennis, has long been advocating serve and volley as a weapon of choice for players.

To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, O’Shannessy believes reports of the death of serve and volley tennis have been greatly exaggerated. Stefanos Tsitsipas is one of those who uses the tactic fairly regularly, while O’Shannessy points to the tactic used by world No 1 Novak Djokovic against No 2 Daniil Medvedev in the final of the Paris Masters in November, when he served and volleyed 22 times, winning 19 of them.

“Djokovic won a stunning 86 per cent of his serve and volley points to completely throw a monkey wrench into the Russian’s monotonous baseline strategy of sticking the Serb in the backhand cage deep in the Ad court,” O’Shannessy wrote on the ATP Tour’s website.

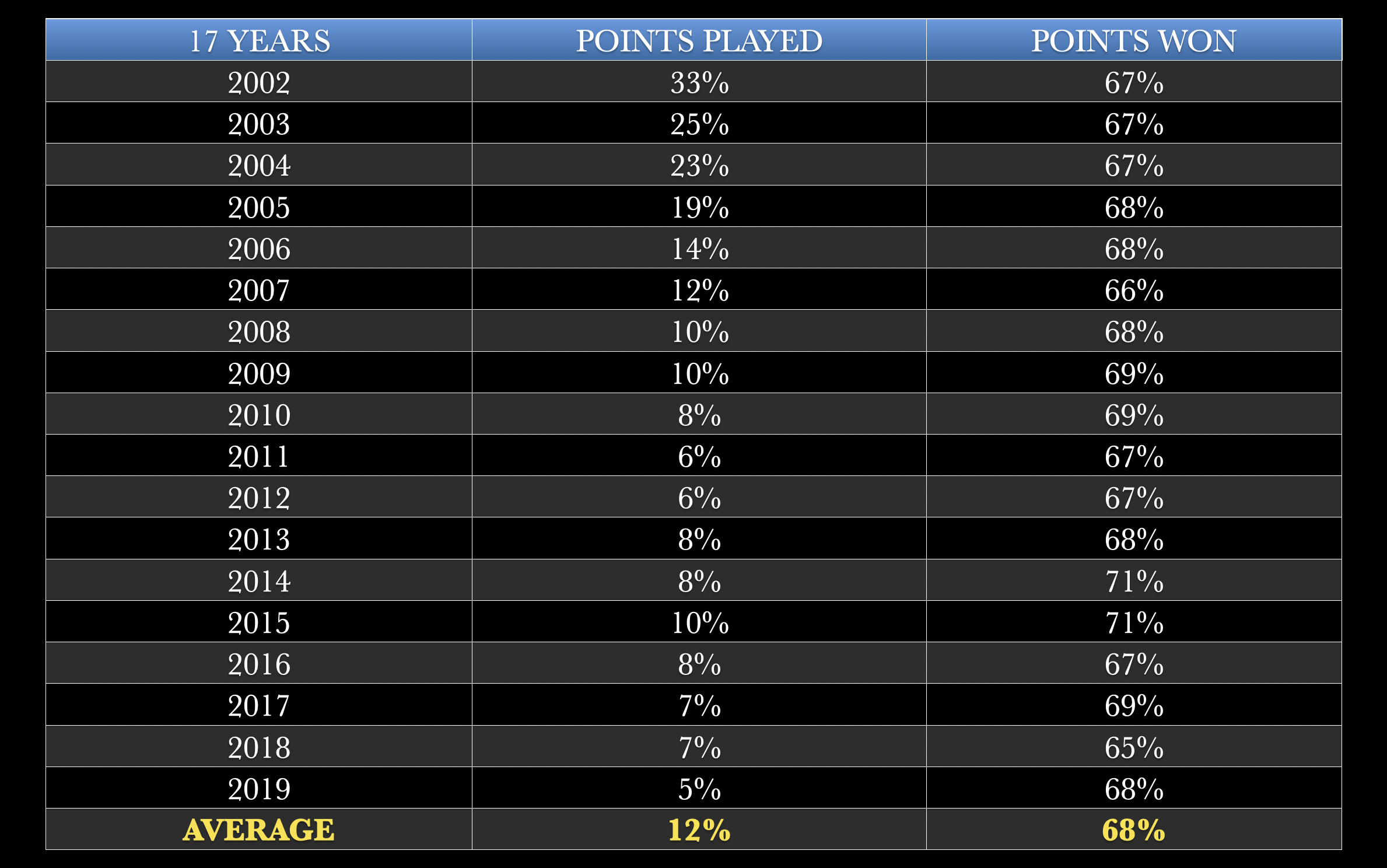

O’Shannessy shared two sets of stats with Tennis Majors to illustrate why serve and volley is still a force for good in the men’s game.

In the first one, he illustrated the percentage of serve and volley points played and won by players at Wimbledon since 2002 (the year they changed the grass, making it slower), to 2019. Though the percentage of serve and volley points played has dropped from 33 percent in 2002 to just 5 percent in 2019, what’s fascinating is that the percentage of serve and volley points won has barely changed at all; 67 percent in 2002 and 68 percent in 2019.

Now, just because the percentage of serve and volley points has remained almost the same does not mean that serve and volley is as useful as it was 20 years ago. With only five percent of points being serve and volley in 2019, simple maths will tell you that the number of points won played with serve and volley, not to mention won, has dropped a lot.

Serve and volleying, as a tactic, though, remains important. It’s just that, since everyone returns and passes so much better than they ever did, it’s more difficult and is generally used as a surprise tactic.

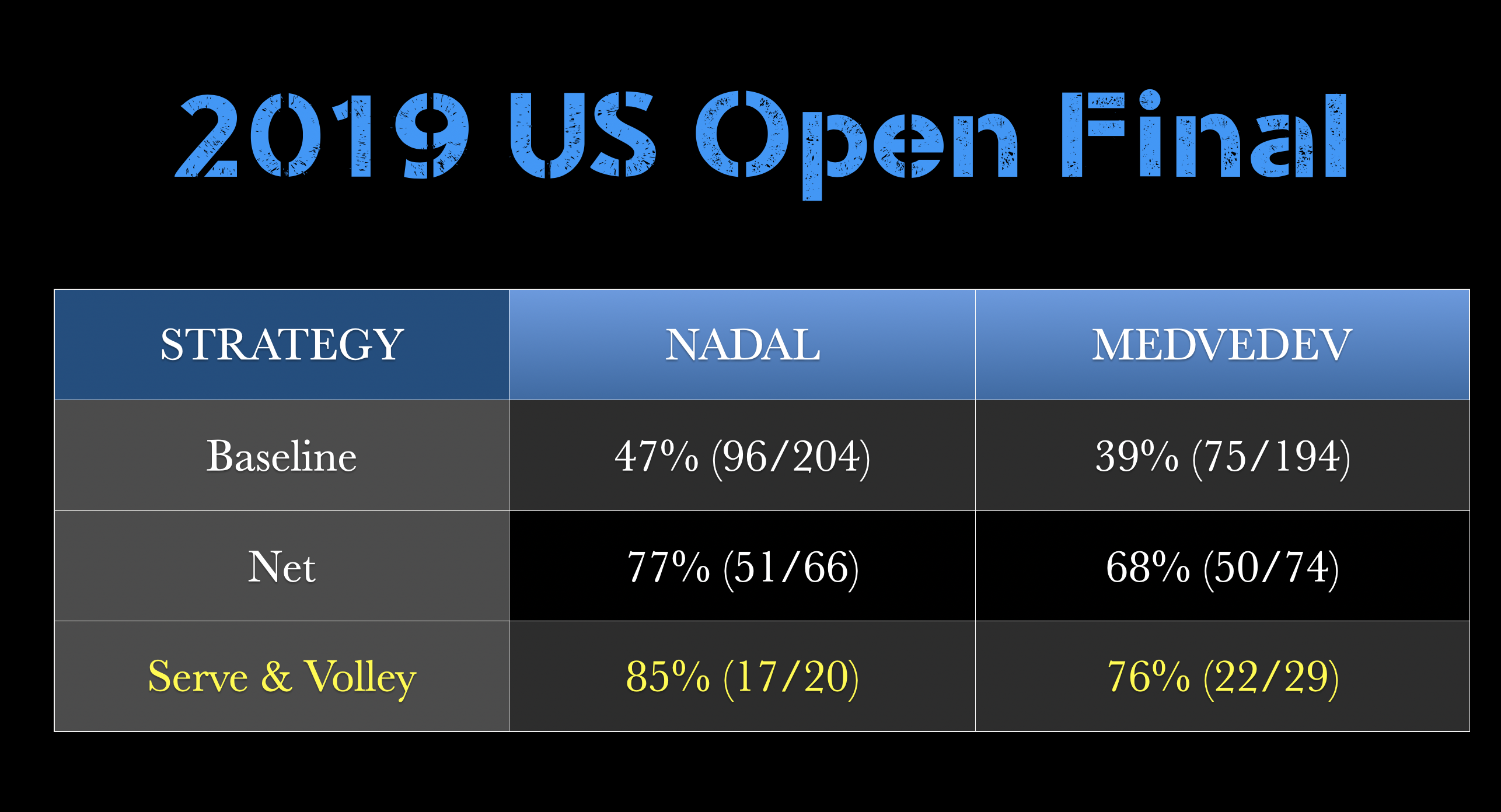

O’Shannessy also shared stats from the 2019 US Open final, when Rafael Nadal beat Daniil Medvedev in five sets, utilising serve and volley in superb manner.

Carillo: “It would take someone terrific, but yes, it’s possible”

Growing up in New York, Mary Carillo had the best seat in the house as she watched her childhood friend John McEnroe serve and volley his way to world No 1 and seven Grand Slam titles.

American Carillo, one of the most respected television pundits in the tennis world, won the French Open mixed doubles title with McEnroe in 1977 and marvelled at his volleying skills. “What was amazing was how well McEnroe could handle (Bjorn) Borg’s topspin,” Carillo told Tennis Majors.

“I think it is possible. I think what changed serve and volley in a very big way was the two-handed backhand. That, to me, changed everything. I was taught and I taught for the late, great Harry Hopman and the whole idea – and this was when three of the four majors were on grass anyway, but the whole point was serve into the backhand, get to the net, put away the volley. And now I mean, how many, especially on the women’s side, how many of their back hands are better than their forehands? Now, your first volley is probably going to be defensive.

Serve into the backhand, get to the net, put away the volley…

Mary Carillo

“Can it happen? Yes. But it it would take it would take someone terrific, it wouldn’t just be a serve because plenty of people can serve aces, especially on the men’s side.

“You’d have to go body, you have to make them hit a return that’s either defensive or neutral and then maybe you’ve got a shot. But the days of Stefan Edberg, who would roll in his service to get tight to the net for his first volley, that’s not going to cut it. The other thing too is, people stand so far back to return now. String technology, racquet technology, the physicality of the game, the court dimensions have actually changed. So if you want if you want to serve and volley, you’ve really got to know your onions.”

Rafter: “I think someone like Pete (Sampras) could probably do it”

Rafter said if anyone could do it would be someone playing with the skills of Pete Sampras.

“Sampras was different,” he said. “He just had a massive serve, great athlete, when he wanted to move. Wasn’t a traditional serve and volleyer but serve and volleyed the whole time. I think someone like Pete could probably do it.”

But Rafter said the fact that it takes time to learn all the subtleties involved in serve and volleying makes it even tougher for someone new.

“It would be really interesting to see but the problem with the serve-volley game, is that when (a player is) 18, 19, you go: ‘right, we’re going to work for the next couple of years on serve-volley’. There’s a lot of nuances about the game. Where you position, where you hit, how hard you hit the serve to get to the net in time, (knowing the) weaknesses in the players.

I would serve to get a volley, not serve to get an ace

Pat Rafter

“I’d serve to get a volley, not serve to get an ace. So I don’t know. Maybe you don’t learn that in two years, you learn that from the time of 14, getting passed the whole time. And then by the time you’re about 22, you finally realise that this is how you play the game. That’s how long it took me. So unless you’re going to play it at a young age, I don’t know. But until the courts become slightly quicker, again, I don’t know how relevant it’s going to be.”

Sergiy Stakhovsky, who this week retired, was one of the few players who regularly served and volleyed, his most notable win coming at Wimbledon in 2013 when he upended the defending champion Roger Federer.

Dustin Brown, who once beat Nadal at Wimbledon, was another more recent exponent of the tactic. Others have dabbled – some continue to do so – and Cressy believes it can be done, at the very top level.

“I made that decision quite a long time ago, when I was 14 years old, that I wanted to be a serve-and-volleyer,” he said. “No one has been able to convince me to do otherwise, even though a lot of people have tried to make me a baseline player or after my serve, serve plus one.

“But I’ve developed huge self-confidence, especially because it was my decision and not the decision of anyone else to play that style of play, and it’s my dream to be able to make it a common style of play at this stage. It’s my dream to be able to instil that in everyone’s belief.”