1968, Open era: The moment tennis opted to become a modern sport

With seven governing bodies and unity still seemingly impossible, tennis has never been quite so disorganised or disjointed. In the first of three special features, we look at the revolution of 1968, when tennis finally entered the modern era.

Open Era – Major Features

Open Era – Major Features

March 30, 1968. Probably the key date in tennis history. Members from the International Tennis Federation (known at the time as the International Lawn Tennis Federation) were gathered at the Automobile Club de France headquarters, in Place de la Concorde in the 8th district of Paris, to sign the Open era’s birth certificate. Here was the revolution. The modernity. For the first time in tennis history, federations were to authorise professional players to play alongside amateurs in the same tournaments. This change would eventually prove to be the first step in making tennis what it is today: hugely popular and with the best players in the world participating in the biggest tournaments, for an even bigger show.

But everything has not been easy. Far from it. Before 1968, tennis was divided into two clans: the amateurs, who were playing tournaments without prize money, and the pros, who were paid by sponsors for their appearances. The pros were not allowed to play the Grand Slam tournaments – still tennis’ Holy Grail – but the Grand Slams were not offering any remuneration. At that time, the sport’s nobleness was considered more important than anything and the collective good thinking was that you didn’t need to win money to be considered a great champion.

“In fact, federations and national associations, which were organizing the biggest tournaments in the world, discreetly paid amateur players under the table to have control of them,” journalist and tennis historian Steve Flink told us. “And these players were called shamateurs. These amateurs were not earning enormous amounts of money, but enough to maintain their status and play the most prestigious tournaments like Wimbledon and Forest Hills.”

In his autobiography, My Story: A Champion’s Memoirs, published in 1948, Bill Tilden, American player and 10-time Grand Slam winner from 1920 to 1930, wrote :

“If tennis is to realize its full potential, it must find a solution to the professional/amateur problem which has plagued it for many years. Only through such a solution can there be free competition among not just a few of the great players of the world – but among all of them. The sporting public want to see the best. It doesn’t give a hood whether that best is amateur or professional.”

Tilden had already understood his sport’s situation, 20 years before the start of the Open era.

Despite their prestige, amateur tournaments – among them Wimbledon, the French Open or the US Open – were more and more deserted during the 1960s as players turned professional, allowing them to earn much more money. Sponsors were organising tours with the best professional players in the world, with a huge cheque given at the end. The three biggest professional tournaments were the Wembley Pro, the US Pro and the French Pro. Rod Laver, one of the sport’s legends, was an amateur player from 1956 to 1962, before turning pro in December 1962, a decision that meant he could not longer play in any of the Grand Slams from 1963 to 1967… There was then an exodus of the best amateur players, who would no longer depend on their Federations, and in the process earn more money. Leaving prestigious tournaments like Wimbledon or the French Open, they were hoping to initiate a system change.

“The public wanted to see all of the best players—amateur and professional—competing against each other,” Steve Flink explained. “But those who had turned pro couldn’t play the most prestigious tournaments anymore. Pancho Gonzalez, Ken Rosewall, Rod Laver: these great names and others were not permitted to play the Grand Slam tournaments. This was an injustice to the fans.”

Tennis is losing itself: the two “clans” had to be reunited.

1960, a first missed opportunity

The Open era could have begun eight years earlier, in 1960. But the coup attempted by the International Lawn Tennis Federation failed. During the summer of 1960, the ILTF gathered in Paris to vote on whether to open tournaments up to both amateurs and professionals. Motion rejected by… a five-vote margin! This loss had been a real shock for players, amateurs and professionals, who were already convinced that the motion would be accepted. National federations still wanted to keep control on amateur players under licences. They were deciding which tournaments their players, paid by them, were going to play each year.

“At this time, national federations were running tennis: players were hired to play for their countries, it was the priority,” journalist and tennis history specialist Joël Drucker explained to us.

Whereas other sports such as soccer, Formula 1 or boxing were beginning or pursuing their evolution toward professionalism and were transforming into real businesses, tennis was staying behind, stagnating and losing popularity.

“The most known events didn’t have the best players, one of ATP founding fathers Jack Kramer wrote in his autobiography The Game – My 40 Years In Tennis. Tennis was a wonderful sport, but with amateurs and professionals in two different spots, it could not have the visibility it truly deserved.”

Players waited eight long years before that finally became a reality on March 30, 1968, with the key signature from the International Lawn Tennis Federation, formalising the Open era birth and the reunification of amateur and professional players. In this eight-year period, federations had lost their best players, who turned pro and were feeling that change was in the air. At the end of 1967, trying to make things evolve, and against the ILTF’s opinion, the British Lawn Tennis Association approved a reform to organise in Great Britain tournaments opened to professionals and amateurs, including Wimbledon, as soon as 1968. This brave decision gained the support from several federations and pushed the ILTF to change the face of tennis, on March 30, 1968.

Bournemouth, 1968: revolution completed

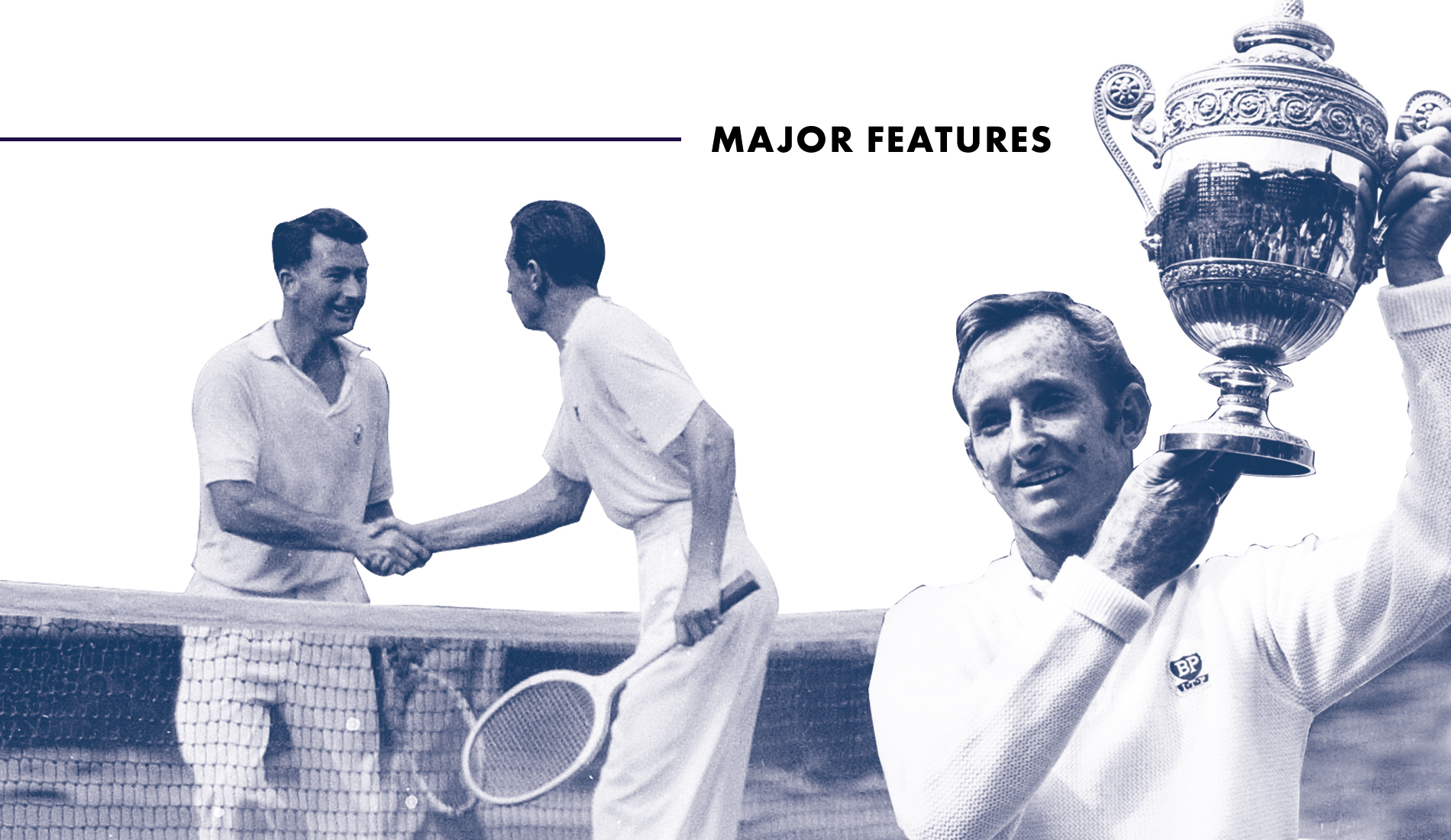

The first official tournament from this new era was held in Bournemouth, England, from April 22 to 27, 1968. One amateur stood out: British Mark Cox. He beat two professional stars: Roy Emerson and Pancho Gonzalez. Cox didn’t win the tournament; another star of the time, Ken Rosewall, prevailed over Rod Laver in the final. It was a success for the organisers. Ticket sales were six times greater than those from previous years. “If anyone doubted that Open tennis would galvanise public interest overnight, here was their answer”, wrote prominent British journalist Linda Timms in World Tennis the day after the final.

“The Open Era has been a big step forward in tennis,” Steve Flink told us. “It immensely contributed to this sport’s popularity. The public could finally see all of the best players in the world together. Ken Rosewall took the first Grand Slam tournament of the Open Era at Roland Garros in 1968. Rod Laver was victorious at Wimbledon that same year. Tennis fans rejoiced as they watched these enduringly great players perform again on the premier stages of the sport!”

The quality of tennis played all over the world quickly rose. The interest from the public and sponsors for these tournaments grew. The incomes and tennis professionalism developed from the early seventies. Players would see in this modern era the opportunity to build a real business, to earn more money. But this quest for power and recognition would create a new separation, between men and women. Thinking that they were the most popular and bankable, these men would think of their own development plan. The starting point for a power split and a fight for equality in treatment concerning money. An issue tennis is still navigating through.